Resources

Click on the tabs below to view the content for each chapter.

Chapter 1

Document 1.1 Frank Bellew, “A Dangerous Novelty in Memphis” (1862)

This cartoon illustrates the rising tensions within Memphis, a city recently occupied by Union forces. A restaurant owner and a Union soldier argue over the availability of “mutton” featured in a window advertisement. Because of the scarcity of food in the South, the soldier warns of a riot if the public discovers this advertisement and bounty.

Source: Harper’s Weekly, June 21, 1862: 400.

Document 1.2 (378) “Resistance to the Draft in Indiana: An Enrolling Officer Shot” (1863)

Draft resistance was widespread throughout the Union and in some areas of the Confederacy. Midwestern resistance was especially fierce in counties with workers who earned lower-than-average wages, a high percentage of foreign-born residents, and those areas with high Democratic voting populations in the predominantly Republican states. Resistance to the draft took on a myriad of forms, some more violent than others. Some men hid out in the woods to avoid enrollment in the draft. Civilians and potential draftees frequently heckled draft officers or forced them out of town. Women threw eggs or other household products at enrolling officers, and crowds of women and children often blocked the entrance to towns or households. In June 1863, this newspaper article described the shooting of an officer who was attempting to enroll men into service in Indiana.

Document 1.3 (367) “A Letter from One of the Rioters” (1863)

The most infamous rioting of the Civil War took place in New York during the week of July 13, 1863. The city had been filled with antiwar and antidraft sentiments for many weeks, and men’s fears of the draft only intensified when they received reports from the battle at Gettysburg. When draft lottery drawings began on July 11 the crowd grew hostile. The working-class poor of the city joined with Peace Democrats in declaring the draft a product of the “rich man’s war” and refused to fight. Workers were angry that rich draftees could purchase a replacement and avoid military service, and they resisted the idea of fighting to free African Americans. The lottery continued on July 13, and the crowd of mostly Irish and German immigrants decided to shut it down. Workplaces were nearly empty as workers gathered to resist. This letter to the editor of the New York Times illustrates the tensions created by the $300 commutation fee that became a major complaint in the draft riots.

Document 1.4 (622) “The Riots in New York” (1863)

Poor workers rioting in New York in July 1863 also feared that freed African Americans would take their jobs. The violence quickly became a bloody race riot, and African American homes, businesses, and individuals were common targets of the mob. The violence shifted from anger at the government to fear of racial mixing and economic competition. It took the intervention of Union troops on July 16 to return the city to order. More than 100 people, many of them African Americans, died during the week-long melee, and hundreds more were injured. In this newspaper article, a Philadelphian comments on the horrors of the riots, declaring them “un-American.”

Document 1.5 “The Rioters Burning and Sacking the Colored Orphan Asylum” (1863)

During the New York City draft riots, the Colored Orphan Asylum in the Nineteenth Ward was burned. The children barely escaped as the mob tried to kill them. Elsewhere in the city, black men and women were hanged from trees and lampposts, shot, and burned in their homes. This engraving in Harper’s Weekly depicts the burning of the orphanage.

Source: Harper’s Weekly, August 1, 1863: 493.

Document 1.6 “The Riots at New York” (1863)

During the New York City draft riots, the draft office was burned, and the mob moved on to destroy the homes of wealthy Republicans and abolitionists. They also targeted pro-Lincoln businesses and newspapers, such as the New York Tribune. Republican-owned factories were looted and workers’ entry blocked. This engraving in Harper’s Weekly includes illustrations of five scenes from the riots. Depicted are the ruins of a downtown office, a fight between rioters and military officials, a scene at the newspaper office, a riot scene at a drug store, and a lynching.

Source: Harper’s Weekly, August 1, 1863: 484.

Document 1.7 (518)“Riots and Mob Law” (1863)

Even journalists for scientific publications commented on the disgraces that occurred during the New York City draft riots. This article about mob behavior was sandwiched between an article about simple locomotive engines and another about experiments with boiling water.

Document 1.9 (634)“The Bread Riot in Mobile” (1863)

In 1862 and 1863, bread riots erupted throughout the South, in Atlanta, Savannah, Milledgeville, Macon and Columbus in Georgia, and in Salisbury, North Carolina and Mobile, Alabama. Women and families bore the brunt of declining homefront conditions and with little prospect of raising crops by themselves, many rural women moved to cities seeking wage work. Burgeoning urban populations placed stress on food production and transport systems. Faced with food shortages and inflation, women and men rioted to express their dissatisfaction with the government and living conditions. The press frequently portrayed the protests as women’s riots, although men certainly participated. Below, a journalist describes the rioting women in Mobile, Alabama, who had recently protested the lack of available foodstuffs.

Document 1.10 (1351) Anna Elizabeth Dickinson, What Answer? (1868)

Anna Dickinson, who was active in the antislavery and women’s rights movements, wrote the following account of the New York City draft riots.

Chapter 2: Southern Dissent

Document 2.1 “Stand by the Constitution and the Union” (1861)

Wartime disaffection among southern whites had solid roots in the early secession crisis. Most white Southerners, three-fourths of whom owned no slaves, made it clear in the winter 1860–61 elections for state convention delegates that they opposed immediate secession. For example, a few weeks before Virginia’s vote for delegates to the state’s secession convention, a mass meeting of working class men in Portsmouth drafted and unanimously approved the following resolutions to stand by the Union. Nevertheless, state conventions across the South, all of them dominated by slaveholders, ultimately ignored majority will and took their states out of the Union.

Document 2.2 (538)“To Henry Bell” (1861)

In 1861, James Bell had six grown children, all loyal to the Union except one son, Henry, who moved to Mississippi and joined the Confederacy with his cousin Andrew Lowrimore. Writing to Henry three months after Alabama left the Union, James expresses hope that he will cease to be a “Cecessionist”. The family never had an opportunity to reconcile. While Henry joined the Confederate army, four of his brothers enlisted on the Union side. Three did not survive the war. Henry succumbed to disease in Chattanooga. James died at home in September 1862.

Document 2.3 (737)John Aughey, The Iron Furnace (1863)

Southern enlistments declined rapidly after the First Battle of Bull Run in July 1861. Men were reluctant to leave their families in the fall and winter of 1861–62, and many of those already in the army deserted to help theirs. The Confederacy’s response to its recruitment problems served only to weaken its support among plain folk. In April 1862, the Confederate Congress passed the first general conscription act in American history. But desertion became so serious by the summer of 1863 that Jefferson Davis begged absentees to return. If only they would, he insisted, the Confederacy could match Union armies man for man. But they did not return. In this excerpt, a preacher talks about his own attempts to evade conscription.

Document 2.4 (323)“To Maj. C.D. Melton” (1863)

Many thousands of deserters joined antiwar and anti-Confederates organizations that had been active in the South since the war’s beginning. Some formed guerrilla bands, often called “tory” or “layout” gangs, that controlled vast areas of the southern countryside. They attacked government supply trains, burned bridges, raided local plantations, and harassed impressment agents and conscript officers. Writing from South Carolina in August 1863, one Confederate Major described the rising militancy of groups of deserters.

Document 2.5 (1583)“To the Superintendent of Conscription” (1863)

Writing from North Carolina in September 1863, a commanding officer and inspector complains to a superintendent of conscription about the rising numbers of deserting soldiers and highlights the difficulties of locating and capturing deserters.

Document 2.6 (269) “To Maj. Gen. J.B. Magruder” (1863)

Writing from Texas in October 1863, a Brigadier-General with the Confederate Army warned another military leader of the increasing problem of desertion that would surely end in more bloodshed. By 1864, the draft law was practically impossible to enforce and Jefferson Davis publically admitted that two-thirds of Confederate soldiers were absent, most of them without leave.

Document 2.7 (238) “To the Secretary of War” (1864)

Writing from Tennessee in 1864, this general tells the Secretary of War that some of the locals in the South would prefer to join the Union Army if they were only allowed to form their own regiments. His letter illustrates the complexities that surrounded the recruitment of soldiers.

Document 2.8 (432) “To the Georgia Governor” (1864)

Writing from Georgia in February 1864, Samuel Knight complained to the Governor of Georgia, Joseph E. Brown, that few of his neighbors were loyal to the Confederacy, and in fact, seemed sympathetic to the Union cause.

Document 2.9 (287) “To Go or Not To Go” (1864)

In early summer 1864, as the Union army was advancing through northern Georgia toward Atlanta, Governor Joseph E. Brown issued a general call to arms. A newspaper in Milledgeville, then the state capital, published a poetic response from an anonymous Georgia farmer.

Document 2.10 (596) Dennis E. Haynes, A Thrilling Narrative (1866)

Even as deserters took up arms and formed posses, the southern home guard companies committed their own acts of violence against the deserters and Unionists. Dennis Haynes, a Louisiana Unionist who late in the war commanded a unit of federal scouts, recalled in his memoir that a home guard company, led by “Bloody Bob” Martin, terrorized anti-Confederates in western Louisiana.

Chapter 3: Women Soldiers

Document 3.1 (768)Sarah Morgan, A Confederate Girl’s Diary (1862)

Writing in her wartime diary in Louisiana at the age of 20, Sarah Morgan wishes she were a man so she could “don the breeches” and slay the Yankee enemies. If there were only a few southern women in the ranks, they would set the men a good example, she adds, proclaiming: “there are no women here! We are all men!” Although Sarah did not disguise herself as a man to take up arms, numerous women shared her sentiments and entered the ranks of both armies. As for Sarah, she spent the early war years with her mother and sisters in the countryside near Baton Rouge, but they abandoned their home in August 1862 after the Union army sacked it. The women spent the rest of the war in occupied New Orleans.

Document 3.2 Winslow Homer, “Our Women and the War” (1862)

Although some women wanted to be part of the war in the most direct way possible—by fighting—women on both sides of the conflict also created a workforce that tried to outfit and care for soldiers. Aid societies for both the Union and the Confederacy made socks, gloves, pillowcases, sheets, undergarments and whole uniforms. Women organized supplies for the hospitals, which they packaged and sent on, and also prepared and packaged food for the armies. As well, more than 3000 women worked as paid nurses for the Union and Confederate armies. A select few also worked as military doctors and hundreds served as spies for both the North and the South. This engraving in Harper’s Weekly, published in 1862, illustrated some of these roles that women played in the Civil War.

Source: Harper’s Weekly, September 6, 1862: 568–569.

Document 3.3 (3016) Sarah Emma Edmonds, Nurse and Spy in the Union Army (1865)

Sarah Emma Edmonds was one of approximately 400 women who succeeded in enlisting in the army (either Union or Confederate) during the Civil War. She succeeded in remaining in the army for several years and was successful as a Union spy. In two different episodes excerpted below from her autobiography, published soon after the end of the war, she disguises herself as an African American male cook and as a male rebel, and plays both roles convincingly. Disguised as a Kentucky boy, she shoots a Confederate captain in the face and is attacked by Confederate soldiers. In a foreword to the book, the publisher took the opportunity to make the case for women soldiers: “In the opinion of many, it is the privilege of woman to minister to the sick and soothe the sorrowing—and in the present crisis of our country’s history, to aid our brothers to the extent of her capacity—and whether duty leads her to the couch of luxury, the abode of poverty, the crowded hospital, or the terrible battle field—it makes but little difference what costume she assumes while in the discharge of her duties.—Perhaps she should have the privilege of choosing for herself whatever may be the surest protection from insult and inconvenience in her blessed, self-sacrificing work.”

Document 3.4 (3304) Mary A. Livermore, My Story of the War (1887)

In this excerpt from her memoir, Mary Livermore argues that women experienced the same feelings of patriotism as men and made parallel sacrifices during the war. She describes the work of nursing, supplying hospitals and making uniforms, as well as several occasions where women disguised themselves and joined regiments.

Document 3.5 (1139) Susie King Taylor, Reminiscences of My Life in Camp (1902)

Susie King Taylor, a former slave, joined the all-black SC Volunteers, that later became the 33rd US Colored Troops. In her memoir, she recounts her experiences as a woman in the regiment. At first, she was secretary, due to her ability to read and write. Later, she traveled with her husband who soldiered with the 33rd, and then became a nurse and laundress.

Chapter 4: The Domestic Sphere

Document 4.1 (1800)Caroline Cowles Richards Clarke, Village Life in America (1861, 1862)

Caroline Cowles Richards was born in 1842 and lived in Canandaigua, New York, a farming village in the state’s Finger Lakes region, during the war. She kept a diary of her daily experiences. After the war she married Edmund Clarke and died in 1913.

Document 4.2 (991) Mary Boykin Miller Chesnut, A Diary from Dixie (1861, 1865)

Mary Boykin Miller Chesnut of Camden, South Carolina, was the wife of James Chesnut, Jr., a prominent state politician and a U.S. Senator between 1858 and 1860. The Chesnuts were close friends of Jefferson Davis and counted numerous other Confederate politicians and generals as their friends and acquaintances. James Chesnut defended slavery, was the first Southerner to withdraw from the Senate after Lincoln's election in 1860, and served as a Brigadier-General in the Confederate Army.

Document 4.3 “The Girl I Left Behind Me” (1863)

This decorative envelope, measuring 3 × 5 ½ inches, features a soldier bidding goodbye to a woman dressed in stars and stripes, the message “The girl I left behind me” and a verse from the song “A Soldier’s Tear” by Thomas Haynes Bayly. It bears a 3 cent stamp, is addressed to Mr. John F. Se[?], Eldersville, Washington Co., Pa., and postmarked Washington, D.C., June 7, 1863.

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Document 4.4 (5728)Dolly Lunt Burge, A Woman's Wartime Journal (1864)

Dolly Sumner Lunt was born in Maine in 1817 and moved to Georgia as a young woman to join her married sister. She became a school teacher in Covington, where she married Thomas Burge, a plantation owner. When her husband died in 1858, Dolly was left alone to manage the plantation. She kept a diary of her experiences, including an entry about Sherman’s march through Georgia.

Document 4.5 Carte-de-Visite (1863)

This woman wears typical Civil War era dress: a contrasting collar (easily removed for laundering or replacement), wide sleeves and a wide hoop skirt, narrow waist. The center part in her hair and the simple flat hairstyle adds the dimension of width, emphasizing the width of her face. It was usual to stand supported by a chair, which helped the subject remain still for the long exposure time required.

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Chapter 5: Labor Organizations

Document 5.1 (221)Commonwealth Association, “The Industrial Congress” (1860)

From 1846 through 1856, there were annual National Industrial Congresses of labor reformers of various sorts, hosted by different communities around the country. When radical spiritualists attempted to revive the practice in 1860, their timing could hardly have been more flawed. However, the proposal of the Commonwealth Association of New York City demonstrates the breadth of labor radicalism in the city among English-speaking, largely native-born American workers.

Document 5.2 (684)Richmond Shoemakers’ Exchanges (1861)

In an attempt to use sectional feelings to their advantage, cordwainers in the soon-to-be designated Confederate capital united in agreement not to finish the shoe work begun in Northern shops. Employers responded by claiming that the president of the unionists was, himself, a Northerner, and a sharp exchange followed, reflecting the tensions exacerbated by the disintegration of the Union. The union survived, publicly announcing a business meeting months later.

Document 5.3 (741) Emma Hardinge Britten, “The New Party” (1863)

Remembered today largely as a prominent spiritualist, Emma Hardinge Britten was characteristic of the moderate middle class labor reformers who emerged after the war. However, she had been born Emma Floyd and came to the U.S. from the notorious slums of London’s East End, and took up residence with her mother among the antebellum utopians living in the community of “Modern Times” on Long Island. Spiritualism provided this plebeian woman with her opportunity to rise to take on the appearance of a middle class Victorian respectability, with appropriately more moderate politics, which make her prediction all the more an extraordinary reflection of growing sentiment within the movement. Significantly, though, after her prediction of a “New Republican Party” to emerge some years in the future, she campaigned for the reelection of Abraham Lincoln.

Document 5.4 (740) “The Strikes” (1863)

President Abraham Lincoln, who had defended the right of the shoemakers to strike in 1860, saw absolutely no role for the government, even in wartime, to act on behalf of employers as strikebreakers. Employers in the New York shipyards refused to accept union terms, confident that government concerns over meeting contracts with the Navy would force Federal intervention. A delegation of the striking unions went to Washington and met with Lincoln, who pleaded neutrality but promised the workers that the government would hold the companies to the contract, effectively forcing the bosses to settle with the strikers.

Document 5.5 (882) William H. Sylvis, “Labor and Capital are Antagonistic” (1864)

William H. Sylvis, long the secretary of the National Molders’ Union, undertook a broader effort to organizer workers during the Civil War, despite a brief detour taking a company of volunteers to Gettysburg. His efforts to foster cooperation among local unions and to establish standards of solidarity among the unions established the foundations for the National Labor Union he headed after the war’s end. These selections from an address delivered to organized workers at Buffalo, New York in January 1864 sounded the basic themes of his message: that workers needed to organize in self-defense and assert their common interests in opposition to that of their employers.

Document 5.6 (346) “Printers on a Strike” (1864)

By the spring of 1864, the course of the war drove Southern newspapers and their printers into Atlanta. Facing a particularly acute cost of living, printers there asked for a wage increase. The employers replied to “the unreasonable demand made by the Typographical Union” by discharging the men, taking away their draft exempt status, and summoning the military to conscript them. In June, the authorities drafted the workers and placed them under command of Albert Roberts, the editor of the Southern Confederacy and one of the bosses with whom they had clashed. This printers’ company of “Robert’s Exempts,” included union printers from locals across the South and several from Northern locals that had evidently been in the South at the war’s outbreak. This was likely the first instance of an American government’s drafting of strikers and forcing them to return to work under threat of military discipline.

Document 5.7 (665)William S. Rosecrans, “General Order No. 65” (1864)

Military orders to break strikes became immediately controversial for several reasons. Workers supported the war effort and many were veterans who had returned to civilian life. These two orders, issued in the border cities of St. Louis and Louisville were not unique but became particularly obnoxious to the workers who were overwhelmingly one of the most reliably Unionist forces in local politics. William S. Rosecrans, whose headquarters issued the first, was openly allied with the most conservative faction of the local Unionists.

Document 5.8 General Dix, “To Secretary Stanton” (1864)

The spring of 1864 saw a wave of strikes in American cities from the east coast to St. Louis. The draft laws, which allowed for those who could afford it to buy their way out of military service had caused major rioting in several communities the previous summer. For obvious reasons, the army prudently sought to avoid a conjunction of those grievances with those that motivated unions to strike. In this case, General Dix suspends the draft as a massive strike wave hits New York City.

Chapter 6: Commerce and Industry

Document 6.1 (716) Richard Henry Dana, Two Years Before the Mast (1840)

In this excerpt, a young Boston aristocrat describes his experiences on a New England merchant ship and characterizes the working life onboard a shipping vessel. After staple crop exports, shipping was another major driver of American economic growth in the antebellum period.

Document 6.2 (672) Anonymous, “A Week in the Mill” (1845)

Originally published by a young Universalist minister, the Lowell Offering magazine soon picked up sponsorship from the Boston Associates, the owners of the mills. The magazine published only works and articles by the female employees of the mills.

Document 6.3 (670) John Brown, Slave Life in Georgia (1855)

John Brown was enslaved in Georgia and escaped to England via Canada, where he dictated a narrative to Louis Chamerovzow, the Secretary of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society.

A British journalist reflects on the economic interconnections between the north and the south in a workingman’s journal.

Document 6.5 James Henry Hammond, “Cotton is King” (1858)

On March 4, 1858, Southern planter James Henry Hammond delivered a speech to the United States Senate on the topic of the admission of Kansas to the Union under the Lecompton Constitution. His speech, best known as “Cotton is King,” exemplified the powerful role of cotton in the American economy and the blurred lines between Southern slave labor and Northern industrial work.

Document 6.6 Rebecca Harding Davis, “Life in the Iron Mills” (1861)

Written in 1860 and published in 1861, Rebecca Harding Davis’ novella was one of the first major critiques of industrialization. Davis believed that the industrial system created unacceptable class distinctions between white people and distanced man from nature. She criticized industrialization through the twin lenses of white egalitarianism and agrarianism – two ideologies that were rooted in the political culture of the years leading up to the Civil War.

Chapter 7: The Environment

Document 7.1 Joel Cook, The Siege of Richmond (1862)

Farmland took hits from all directions during the war. Because large armies prefer to fight in open spaces, farmlands and pastures became battlefields across the South; as men and animals moved into position they churned up earth. Fields were also optimal spaces for establishing camps. The presence of encamped soldiers compressed still-standing crops and killed them, unless foraging soldiers harvested them first. According to northern journalist Joel Cook, who traveled with Union troops during the Peninsula Campaign in 1862, soldiers were often choosy when scouting for campsites, preferring grass or grain fields. Cook also describes the search in the surrounding wilderness for clean water from springs, a search often thwarted by the muddy or swampy water. Cook goes on to describe the impact of rainstorms that deluged camps and turned roads into impassable mire. These storms did not stir the stagnant swamps, however, as Cook explains—and the “miasm” from the swamps caused disease.

Document 7.2 Timothy H. O’Sullivan, “Troops Building Bridges Across the North Fork of the Rappahannock” (1862)

Civil War soldiers burned bridges in order to obstruct the enemy’s pursuit. Then they rebuilt them. Timothy O’Sullivan, a Union photographer with Mathew Brady’s studio, captured this building process in Fauquier Sulphur Springs, Virginia, as members of the Army of the Potomac’s Corps of Engineers rebuilt a bridge across the North Fork of the Rappahannock River in August 1862. Sometimes soldiers built bridges and roads from scratch, constructing some of the most impressive examples of transportation infrastructure in the nation at that time.

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Document 7.3 James Julius Marks, The Peninsular Campaign in Virginia (1864)

As central constructive elements of earthworks, trees protected soldiers; they also shielded men from harm on the battlefield. Skirmishers and other soldiers under fire were likely to take up positions behind trees because even young saplings could provide protection against musket or rifle fire. Northern journalist James Julius Marks could not believe the damage that a “storm of bullets” did to Virginia’s trees along the Williamsburg road in 1862. Marks also describes the destruction of orchards by camping troops and explains the cyclical restoration of exhausted fields in the shelter of Virginia’s pines. In Marks’s account, even as forest and orchard trees are destroyed by soldiers, pine trees regenerate the land.

Document 7.4 Walt Whitman, “Cattle Droves About Washington” (1864)

Both armies used hundreds of thousands of horses and mules for transportation and other forms of labor between 1861 and 1865. Their enlistment in the war effort impacted the northern and southern farms, plantations, and city streets from which they came. Their absence was felt especially in agricultural fields across the nation, which often lay fallow without the horses and mules to pull plows and haul crops and other materials. Just as horses and mules disappeared from the landscape, so did other domesticated and wild animals. Soldiers purchased or stole cattle, pigs, turkeys, and chickens to supplement their meager rations. Cattle drives, like the massive wagon trains that accompanied Union and Confederate armies, trampled vegetation along roadsides. In the winter of 1864 the poet Walt Whitman was amazed to see droves of cattle passing through the streets of Washington, D.C.

Document 7.5 Timothy H. O’Sullivan, “Camp Architecture, Brandy Station, Virginia” (1864)

Timothy O’Sullivan’s image “Camp Architecture,” taken in January 1864 and included in Alexander Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War in 1866, reveals the extent to which soldiers adorned their log huts with pine boughs and other greenery. This hut, built in winter quarters at Brandy Station, is a small one-room cabin with a portico in front; the portico’s “columns” and the gable end are festooned with pine boughs. In his caption for the photo, Gardner lauded the “ingenuity and taste of the American soldier,” which resulted in well-built and refreshingly decorated quarters. “The forests are ransacked for the brightest foliage, branches of the pine, cedar, and holly are laboriously collected,” he noted approvingly, “and the work of beautifying the quarters continued as long as material can be procured.”

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Document 7.6 “Cold Harbor, Va. View of the Battlefield” (1864)

In this photograph from the main eastern theater of war, showing the ground after the charges at Cold Harbor in June 1864, the aftermath of Grant’s Wilderness Campaign of May–June 1864 is apparent. Deep furrows mark the paths of shot and shell, and lumps of soil and rocks litter the ground. One lone shard of wood sticks up out of the earth.

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Document 7.7 William Henry Morgan, Personal Reminiscences of the War (1911)

William Morgan was a Confederate Lieutenant and described in his memoir the harsh environmental conditions for soldiers, including the summer heat, the winter snow, the muddy roads, and the fear that nightime animal sounds in camp might be enemy soldiers signaling to one another. He describes the destruction of the environment, too, as the bark of pine trees is scraped off to reveal useful sap and trees are lit on fire by marching soldiers. But he also focuses on the beauty and mystery of the southern landscape, its hanging gray moss, wild woods and screaming nighthawks all like “scenes described in fairy tales.”

Chapter 8: Religion in the South

Document 8.1 Rabbi Bernard Illowy, “The Wars of the Lord” (1861)

During the Civil War, Jewish Southerners tended to give their allegiance to the Confederacy and served in the government and the military of the Confederate States of America. There were large Jewish communities in the major cities of the South. Assimilated into Southern society and identified as white, Jewish Southerners frequently adopted proslavery opinion, for which Southern Christian apologists could find legitimation in passages of the Hebrew scriptures. This sermon, given at “National Fast Day” services at the Lloyd Street synagogue in Baltimore on January 4, 1861, proved so popular among the Jewish secessionists that Rabbi Illowy was invited to become the spiritual leader of Congregation Shaarei Hassed in New Orleans.

Document 8.2 “To Rabbi Max Michelbacher” (1861, 1864)

Southern Jews enlisted in the Confederate cause for many reasons. In a racial caste system they enjoyed benefits that they did not have elsewhere, either in Europe or in the North. Jewish immigrants in particular were eager to demonstrate their loyalty to their adopted homeland. And many Jewish families had deeper southern roots and a greater cultural and economic investment in the region than some of its Gentiles. General Robert E. Lee’s correspondence with Jewish religious leaders indicates the respect that Lee had for Jewish soldiers but also the exigencies of wartime. In letters to the Rabbi Max Michelbacher of the Richmond, VA congregation Beth Ahabah, for example, Lee will not grant furloughs to Jewish soldiers in the Confederate Army during Jewish holy days. Letters from Jewish soldiers also convey the difficulties in attempting to observe kosher dietary laws and Levitical observances, particularly problematic in the South where salt-cured and sugar-cured pork was a staple of civilian and military diets.

Document 8.3 Moncure Conway, The Golden Hour (1862)

Southern apologists for slavery frequently employed religious rhetoric to defend the institution. They could use proof texts (scriptural passages taken out of context) or make typological arguments (employing a past biblical precedent to make sense of a present circumstance). But although most religious institutions of the Old South accepted and often endorsed slavery, some religious whites in the South dissented from the mainstream view. White southern abolitionist Moncure Conway published his book The Golden Hour in 1862. The book is a plea for emancipation. Often addressing Lincoln directly, it argues that emancipation will cripple the Confederate war effort and hasten peace. Conway uses the Biblical imagery of Revelations to call for a holy war against slavery.

Document 8.4 “The Conquered Banner” (1865)

Southern Catholic priests and nuns served during the Civil War. Catholic nuns, notably the Daughters of Charity founded in Emmitsburg, Maryland, by Elizabeth Ann Bayley Seton in 1809, served as nurses to both sides, without political allegiance. Even the South’s poet laureate was a Catholic priest, Father Abram Joseph Ryan, a native of Norfolk, Virginia, who also served as a military chaplain. His most famous poem, “The Conquered Banner,” became an anthem of the Lost Cause ideology.

Document 8.5 Thomas Wentworth Higginson, “Negro Spirituals” (1867)

African American slaves appropriated and adapted the liberation themes of the Hebrew scriptures and the Christian scriptures. By means of biblical typology, they imagined themselves to be the recapitulation of the Israelites enslaved in Egypt, awaiting a Moses who would lead them to a new promised land, or they borrowed the apocalyptic language of the Book of Revelation and saw themselves as the Church awaiting the return of King Jesus. These consoling messages, and in some instances coded subversive messages, were employed in the classic spirituals. In 1867, Colonel Thomas Wentworth Higginson published several of these songs. Higginson served as colonel of the 1st South Carolina Volunteers, the first federally-authorized army regiment to be comprised of former slaves, and here describes the all-black regiment singing spirituals while in camp, also interpreting the lyrics.

Document 8.6 John Greenleaf Whittier, “A Word for the Hour” (1861)

Religious opinion throughout the North was deeply divided during the months leading up to Fort Sumter, with many ministers and Christian reformers urging peaceful reconciliation or even acceptance of secession. Antislavery poet John Greenleaf Whittier, a Quaker and pacifist, expressed the views of many abolitionists when in the midst of the secession crisis he penned these lines below in mid-January 1861. But the firing upon Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, which Northerners regarded as a sign of southern aggression, ended all confusion and brought the vast majority of northern Christians solidly behind military force to suppress the rebellion.

Chapter 9: Religion in the North

Document 9.1 Julia Ward Howe, “Battle Hymn of the Republic” (1862)

The immense popularity of Julia Ward Howe’s famous “Battle Hymn of the Republic” suggests the consoling power of this optimistic millenarian message. First penned in late 1861 and published in the Atlantic Monthly in February 1862, then later set to music, it had become by the close of the war one of the most beloved songs in the nation. The song links the judgment of the wicked at the end of time with the American Civil War, and alludes to passages in Isaiah, Revelation, Daniel and 2 Corinthians.

In sermons, speeches and editorials, northern ministers and leaders assured Americans that a sovereign God was using both sides in the conflict to purge the nation of sin. Protestants increasingly came to see slavery as the root cause of the nation’s intense suffering, a blight that had to be removed if all the sacrifice of life was to have ultimate meaning. For example, on the first anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, William Henry Hall, a leader in San Francisco’s black community, spoke at Platts Hall on Montgomery Street in San Francisco and described the Civil War as punishment for the nation’s sin of slavery. Hall also pays tribute to the radical abolitionist John Brown, who was executed in December 1859 after taking up arms against slavery in his raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, and had become a martyr to many abolitionists.

Document 9.3 Abraham Lincoln, “Second Inaugural Address” (1865)

The Civil War must be understood as a theological as well as constitutional and political crisis. The war tested common American assumptions about divine providence and the role of the United States in God’s redemptive plan for the world. The failure of Church leaders to find common ground in the Bible on such fundamental issues as slavery and obedience to the government tested Protestant notions about the sufficiency of private interpretation of scripture. Americans of every stripe, as they surveyed the wreckage of their nation, were acutely aware of the irony that Abraham Lincoln voiced so poignantly in his Second Inaugural Address of March 4, 1865. Both sides, the President observed, “read the same Bible, and pray to the same God; and each invokes His aid against the other.”

Document 9.4 Henry Ward Beecher, “Oration at the Raising of ‘The Old Flag’ at Sumter” (1865)

When Fort Sumter was returned to the Union and the flag was restored there in a ceremony on April 14, the famous Presbyterian preacher Henry Ward Beecher gave the speech below, which thanks God for the seed of liberty and peace that has come from the harvest of war. The rest of the ceremony to restore the flag at Fort Sumter included a passage of scripture read by a chaplain, prayers and a benediction. This sanctification of the flag at the ceremony, and in Beecher’s oration, revealed an unprecedented association of cross and flag: the Civil War had harnessed the energy and resources of countless northern Christians and channeled it into the cause of the Union.

Chapter 10: Reform and Welfare Societies

Document 10.1 Frederick Douglass, “The Future of the Negro People of the Slave States” (1862)

Black Americans not only worked to end slavery, they also championed the ideals of a reformed, truly non-racist American society. Figures like James Forten, Richard Allen, and Frederick Douglass all sought to end slavery and also pave the way for equal citizenship. For example, in 1862, Douglass addressed a reform group in Boston and discussed the end of slavery and the future for black Americans in the United States after Emancipation. He calls for honest wages and a new, respectful relationship between black and white citizens.

Document 10.2 Henry Whitney Bellows, “Speech in Philadelphia” (1863)

As the war progressed, civilians began to recognize the inefficiency of volunteer organizations rooted in the local level. While the efforts of local leaders and volunteers were appreciated, they often miscarried. One common complaint concerned the waste of resources, such as food, clothing, bedding and medical supplies, which were meant for the soldiers, but languished in railroad depots. Inspired by the thought of the men deprived of the basic necessities, a group of northern elites led by Henry W. Bellows organized the United States Sanitary Commission. At the height of its powers, it spread across the North and Midwest acting as a clearinghouse for soldiers and for medical supplies, becoming the largest and most highly organized philanthropic activity that had ever been seen in America. Addressing a large crowd in Philadelphia, at the Academy of Music, the organization’s president describes its work.

Document 10.3 Samuel Clemens, “The Ladies’ Fair” (1864)

The United States Christian Commission began soon after the start of the war, in 1861, and a Ladies Christian Commission launched in 1864 as an auxiliary. Its purpose was to furnish supplies and religious literature to Union troops during the Civil War. It also collaborated with the U.S. Sanitary Commission in providing medical services and supplies, and it held fundraising events across the North. For example, in August 1864, a young Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain) reported on the scene at the Ladies’ Christian Commission Fair in San Francisco. The fair proved a success, netting about $40,000.

The Freedmen’s Bureau, created in March 1865, sought to encourage economic self-sufficiency among the newly freed blacks by establishing farms and plots of land to be cultivated. In addition, it established schools, began to register marriages, provided as supervisors and inspectors for existing plantations, and worked to regulate the hours and wages of the freedmen. This excerpt from a Board of Education report describes the progress in setting up schools for former slaves in Louisiana.

Document 10.5 Mary A. Livermore, My Story of the War (1887)

During the Civil War, Mary Livermore volunteered as an associate member of the U.S. Sanitary Commission. She organized aid societies, visited army posts and hospitals, and coordinated the Northwestern Sanitary Fair of 1863, which raised $86,000. In this excerpt from her memoir, she explains the need for the U.S. Sanitary Commission and its beginnings.

Chapter 11: Higher Education

Document 11.1 Professor R.W. Barnwell, “Letter to the Southern Guardian” (1861)

Southern faculty helped establish cadet corps units that formalized student preparation for combat. These corps grew out of student and faculty desire to do their part in defending the region, as well as reflecting the patterns of pride and honor characteristic of antebellum southern life. In this letter to a newspaper, published on May 4, 1861, Professor Robert Woodward Barnwell praises the conduct of South Carolina College Cadets who were stationed on Sullivan’s Island after the battle of Fort Sumter and guarded the beach against a night attack. Barnwell joined the company in camp as chaplain. He had been the third president of the South Carolina College (1835–1841), was a signer of the Confederate constitution and during the war he served in the Confederate States Senate.

Document 11.2 “Our Flag Is There” (1861)

Institutions of higher learning in the North were far less affected by the war than those in the South. The facilities, buildings, and purposes of Northern colleges and universities were virtually untouched by the ravages of war when compared with their southern counterparts. At many institutions, it was business as usual with fewer students, although some smaller ones closed due to lack of funding or very low student numbers. In general, Northern professors engaged in a rhetoric of suppression of rebellion and freedom for slaves, rather than an eagerness to defeat the South or to defend the glory of the North, while students on northern campuses held a wide range of sentiments toward the war. Many felt disengaged, distracted, or uneasy about it. For example at Yale, out of 400, a mere 13 students enlisted in the war in 1861. However, at Harvard, student James Savage, Jr. and his colleagues began drilling with local companies within days of Fort Sumter. They became a few of the 1311 students and alumni who enlisted and served in the Union Army. Ten percent of them never returned from battle. In this Harvard Magazine editorial dated May 6, 1861 and published in the magazine’s first issue since the battle of Fort Sumter, the editor proclaims that Harvard advocates war, is united against traitors, and that Harvard men will fight as patriots and heroes. He refuses to publish the names of students who have left to fight for the South, calling that a “Roll of Dishonor.”

Document 11.3 Augustus Longstreet, “Report to the Board of South Carolina College Trustees” (1861)

In November 1861, Augustus Longstreet, President of South Carolina College and a slave owner, sent this annual report to the trustees of the college, explaining that students had left en masse for war. In response to this report, the trustees asked the college faculty to provide a list of members of the senior class who should receive diplomas, in spite of the war interrupting their senior year. Some diplomas did not reach the students or their families until years after the end of the war.

Document 11.4 The Morrill Act (1862)

In 1862, Congress approved the Morrill Act (also known as the Land-Grant Act). The federal bill was hardly a new idea when it was passed, but it was one that did not gain traction until after the southern states left the Union. Vermont Senator Justin Morrill had talked for years about the need to establish federal support for agriculture and mechanics education. When Morrill successfully pushed the bill through Congress and received Lincoln’s signature in July 1862, the South was shut out of the first federal support for American higher education. The South’s resistance to the Act before the war and its inability to access the funds until after the war meant that northern campuses would receive unprecedented support at the very time southern campuses were under greatest duress. As mandated by the bill, states were granted 30,000 acres of land in western territories for each of their congressional representatives. Consequently, the formula favored the more populous states, which received larger appropriations. Morrill’s bill allowed for states to then sell, rent, or otherwise derive an income from the scrip to finance the establishment of a new institution or to support existing ones. The legislation, however, required that those institutions receiving the funds must promote the education of agriculturists and mechanics of the state. The Land-Grant Act ultimately distributed over 17 million acres to various states of the Union. It provided a significant source of stability for northern institutions of higher education, although it was not always clear which new or established institutions would receive funds from the Act. Established institutions became fiercely competitive with one another to assure their institutions would clinch a hold on the land-grant funds.

Document 11.5 Irdell Jones, “The South Carolina College Cadets” (1901)

Irdell Jones was a junior at the South Carolina College (later the University of South Carolina) and the Second Lieutenant of the South Carolina College Cadets on the eve of the Civil War. The trustees of the college had resolved at a meeting on December 3, 1860, that it should be permitted for students to organize a military company under the direction and control of the faculty. In this account, which he published in The News and Courier in 1901, he recalls the student excitement on campus about the impending war.

Document 11.6 John C. Sellers, “To Mr. E. L. Green” (1912)

In this letter written on March 25, 1912, John C. Sellers recalls the aftermath of the war at the University of South Carolina (the new name for South Carolina College from 1866 onward), including the presence of wounded students with missing limbs.

Chapter 12: Military Schools

Document 12.1 “Report of the Superintendent of the Virginia Military Institute” (1860)

The rising sectional tensions of the 1850s encouraged the establishment of even more military schools and civilian institutions began to teach courses in military studies and create drill companies among student bodies. Then on December 2, 1859, the Virginia Military Institute Corps of Cadets served as the escort of Virginia governor Henry Wise at the execution of abolitionist John Brown in Charles Town, Virginia, with VMI Superintendent Francis H. Smith giving the final command at the gallows. The next month, Smith submitted a report to the Virginia Senate and House, summarizing the conduct of his cadets at the execution. Although the firing on Fort Sumter was still more than a year away, Smith quotes one Virginia mother’s statement that she would willingly give her sons to the southern cause during a civil war.

Document 12.2 “West Point Cadets” (1860)

The growing sectional crisis had a profound impact on America’s national military academy at West Point. Each state from the Union was represented in the cadet ranks and so, after the first states left the Union during the winter of 1860–61, the Corps endured numerous resignations as cadets left to serve their now seceded states. By the time of Fort Sumter, nearly all the southern cadets and professors had departed, drastically reducing the numbers at the Academy. Like southern military schools, it remained open during the war but had difficulties in maintaining full student enrollments and faculties.

Source: New York Illustrated News, October 27, 1860.

Document 12.3 “The Engineer Corps at West Point in Their Dormitory” (1861)

Graduates from West Point had the most impact on the leadership of both the Union and Confederate armies, with over 260 alumni serving the Union and 640 serving the Confederacy. But lack of qualified faculty and the allure of volunteer commissions led to a dramatic increase in failures and resignations during the war years. Academy administrators even thwarted a Congressional proposal to abolish the school in 1863.

Source: Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, February 9, 1861.

Document 12.4 Thomas Rowland, “Letter of a Virginia Cadet at West Point” (1861)

Seventeen year old Thomas Rowland from Alexandria, Virginia was appointed as a cadet to the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1859. He excelled as a cadet, ranking first in his class of 42 members. But he could not graduate with this ranking because he resigned his commission to join the military forces of Virginia after it seceded from the Union in April 1861. His correspondence with his family reveals the difficult decision that he and other West Point cadets had to make, as their loyalty to their friends and their institution often conflicted with their loyalty to their home communities.

Document 12.5 “Cadet of the Virginia Military Institute in Marching Outfit” (1864)

As manpower shortages ravaged the southern ranks and Union forces pushed deeper into the South, several Confederate commanders reluctantly called upon the services of local military schools to augment their undermanned forces. Most often, cadets functioned in the role of a “home guard” by either searching for deserters, escorting prisoners or guard detail. Cadet enthusiasm waned when they finally confronted the realities of life on the campaign: bad weather, fatigue duty and endless footsore marches across the countryside. This illustration of a Virginia Military Institute cadet in his marching outfit accompanied an account of the Battle of New Market, Virginia, on May 15, 1864.

Source: Battles and Leaders of the Civil War , Volume 4 (New York: The Century Co., 1884), 480.

Document 12.6 John D. Imboden, “The Battle of New Market” (1864)

By the later years of the war, the need for manpower within the Confederate forces became so great that military academy cadets were compelled to fight in pitched battle. The most famous of the instances occurred on May 15, 1864 when 257 cadets from VMI helped turn back a Federal Army under General Franz Siegel at the Battle of New Market. Ten cadets were killed during the engagement, which Brigadier-General Imboden describes below. Cadets from SCMA and GMI also distinguished themselves in fighting at the Battles of Tulifinny and Resaca respectively, while the corps of cadets from the University of Alabama contributed in smaller skirmishes during the latter campaigns of the war.

Document 12.7 “Report on SCMA Cadets” (1865)

As the Federal Armies closed in around the Confederate stronghold of Charleston, home of the South Carolina Military Academy (SCMA), local commanders reluctantly called the South Carolina Corps of Cadets into service to protect the city. In December 1864, the cadets fought a brief but intense skirmish with Union troops at Tullifinny Creek near a critical railroad juncture. After a three hour-long battle with Federal troops, the cadets drove them from the field. Several cadets were wounded. The commander of the cadet detachment, Major James B. White, submitted this report, dated December 12, 1865, to the Chairman and Board of the SCMA, detailing the events of the campaign and the deportment of the cadets.

Chapter 13: Military Medicines

During the war, there was no love lost between sectarians (homeopaths and “eclectic” physicians were among the most organized and numerous) and allopaths, who were known for their tendency to favor drastic or “heroic” therapy—for example, bloodletting, inducing vomiting and defecation, and vigorous administration of harsh mineral drugs. Below, an eclectic physician attacks allopathic army surgeons. Sectarians wanted more of their members allowed into the military, so they tended to disparage the practices of allopaths.

Document 13.2 “The Eclectic Practice of Medicine” (1862)

Allopathic physicians considered the sectarians to be quacks. The leaders in the Union and Confederate medical departments were allopaths and so were most physicians who were allowed into the military as surgeons. Below, an allopathic physician attacks eclectic practitioners. Such constant and acrimonious bickering among allopaths and sectarians about which group provided superior treatment eroded the image of physicians as trusted and knowledgeable caregivers during the war. The preexisting doubts that troops had about the abilities of surgeons were exploited by each faction, each with its own agenda to press.

Document 13.3 “One Hundred and Twenty Ounces of Quinine Recovered” (1862)

President Lincoln’s imposition of a naval blockade of the Confederate states became more efficient as the war progressed. Among the items classified as contraband were medical supplies. In response, medicines were smuggled into the South from the North—often by speculators who sold the goods to druggists or medical purveyors—or snuck into southern ports by blockade runners. Below, a northern newspaper describes the capture of southern drug smugglers.

Document 13.4 “Speculative Prices” (1862)

After crossing the blockade, cargoes of smuggled drugs were typically auctioned to druggists or speculators from whom medical purveyors were then forced to purchase. At times, medical purveyors were authorized to seize goods from speculators and pay them only the cost price. Some drugs were imported for government use, but disputes over the price could lead to purveyors impressing the goods and the government determining a “fair valuation.” Below, a blockade-runner asks for a better price from the Confederate Medical Department.

Document 13.5 “Army Hospital Supplies” and “An Order of Surgeon-General Hammond” (1863)

The official military medical supply lists in use at the start of the war were developed by medical officers in the regular armed forces of the United States and reflected the military’s needs as seen by practitioners of regular (orthodox or allopathic) medicine. In 1862, the Union Army liberalized its practices to address the needs of its many physicians who had only recently left civilian practice for the military. But the standard supply tables still fell short in terms of overall selection. Below, a trade journal defends the supply table against its many critics and then two months later reports on the recent order by Surgeon General William Hammond of the Union Army, a progressive allopath, to remove certain drugs from the supply table on the grounds that they were being misused by surgeons.

Document 13.6 “The Other Side of His Hammock” (1863)

Medical practice was largely unregulated in civilian life, such that practically anyone could claim expertise and treat patients. Lax standards accounted for a great many unqualified physicians entering the military as surgeons early in the war. Treatments at the time were not notable for their success, and many troops, especially those from rural areas where physicians were scarce, were accustomed to treating themselves. In an article from 1863, Harper’s Magazine mockingly narrates a story about a navy surgeon.

Document 13.7 George H. Hepworth, The Whip, Hoe, and Sword (1864)

Like this Union chaplain, soldiers often commented that surgeons prescribed exactly the same thing for every patient regardless of the illness or gave different remedies for patients who had exactly the same symptoms. Quinine, calomel, and blue mass or blue pills were the usual medicines mentioned in such accounts. Troops sometimes made light of the situation by giving their surgeons nicknames like “Old Salts” or “Opium Pills” or attaching lyrics like “Come and get your quinine” to the notes blown by the bugler to announce sick call.

Particularly valuable drugs during the war included chloroform and ether, which were used as anesthetics for surgery or other painful procedures, and opium and morphine, which helped relieve pain, suppress cough, and reduce the severity of diarrhea. In this account, a wounded Stonewall Jackson receives chloroform.

Document 13.9 Stiles Kennedy, “Turpentine as a Remedial Agent” (1867)

Quinine—sometimes mixed with whiskey—was well recognized for its remarkable specificity and effectiveness in preventing and curing malaria (commonly called “intermittent fever” or “periodic fever”). But because the South had no preexisting large-scale drug industry, the unreliability of existing sources of medical supply and the ever rising cost of goods forced the Confederacy to commence the collection of native resources, especially plants, from which medicines could be made. Here a Confederate surgeon describes the treatment of malaria with tree bark.

Chapter 14: Civilian Healthcare

Document 14.1 “The Physician as a Citizen” (1861)

Civilian healthcare differed greatly to military healthcare during the Civil War era. For all its faults, the military paradigm had its advantages: sophisticated general and specialized hospitals, the emergence of the professional nurse, an improved ambulance service, surgeons trained and experienced in trauma and emergency surgery. For those Americans at home or the farm during the era, the state of medicine was less progressive. Nonetheless, in an editorial at the beginning of the Civil War, the American Medical Times appealed to their readers’ sense of patriotism, suggesting they become involved in the war effort for the public good and the good of their discipline.

Document 14.2 “Suggestions to Nurses” (1861)

Ailing soldiers were likely to treat themselves by relying on techniques they learned before their military services or remedies sent from home, or cures suggested around the campfire by comrades. And citizens did not hesitate to send newspapers their own recommendations for medicating soldiers, like this southern citizen who recommends a treatment for maggots in wounds.

Document 14.3 “Lincoln as Alchemist” (1861)

Patent medicine vendors took advantage of the Civil War and incorporated martial and patriotic symbolism into their advertising. Likewise, makers of patriotic items incorporated patent medicine motifs into their products, taking advantage of the popularity of the medicines in American culture at that time. Below, in the detail from a patriotic envelope, Abraham Lincoln is portrayed as a pharmacist/alchemist with the names of Union generals on the products that surround him in his laboratory. The products are meant to cure the illness of secession. Leading Confederate personalities are shown being hanged in specimen bottles.

Source: James M. Schmidt Collection.

Document 14.4 “Anti-Typhus Remedy” (1863)

Applications to the United States Patent Office for medicines increased significantly during the Civil War. Several of the “improved medicines”—as they were billed—were born of perceived wartime necessity, but most were for use in the home or on the farm. Letters patent did not endow the inventions with any more scientific merit than the secret nostrums and proprietary medicines of the era, as seen in the remedy below.

Document 14.5 E. S. Gaillard, The Medical and Surgical Lessons of the Late War (1868)

After the war, Americans in the North and South encountered quackery in the continued influence of patent medicines. Just as they had during the war itself, patent medicine firms marketed their wares specifically to Civil War veterans in the post-war years, and counted on testimonials from veterans to prop up their “snake oil” to the American public. The stakes were high: patent medicine sales grew to nearly $80 million by the turn of the century. Patent medicines were especially popular in the South, which did not have the same maturing base of pharmaceutical industry that the North enjoyed. However, one person, at least, believed that the long-lasting impact on the war was to show southern citizens that they could live without these quack medicines, having survived the blockade. Below, a former Confederate surgeon tries to explain this particular lesson of the war for all civilians and veterans.

Document 14.6 WPA Slave Narratives (1936–1938)

Slaves were not completely dependent on their owners and overseers for their medical care, nor were they passive recipients. They retained beliefs and practices born of their African roots and were inclined to trust in their own remedies, including plants, herbs, and minerals. White orthodox physicians reported on the more successful slave remedies in period medical journals. Decades later, the narratives by former slaves gathered by the Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration often include descriptions of favorite remedies and opinions on practitioners.

Chapter 15: Slave Emancipation

Document 15.1 “Acting as Slave-catchers” (1861)

Slaves took advantage of the intense disruption of war and by August 1861, more than 900 fugitives had sought and gained protection with the Union forces. But before the enactment of a new article of war on May 13, 1862, prohibiting army officers from returning fugitive slaves to their owners, soldiers were sometimes forced to act as slave-catchers. Below, Union soldiers despise the order to return slaves to their masters.

Document 15.2 Benjamin Butler, “To Lieut. Gen. Winfield Scott” (1861)

Early in the war, Major-General Benjamin Butler classified slaves who were used in the Confederate military effort as contraband. Here he describes at length the growing number of fugitive slaves, women and children among them, seeking refuge within his lines, and while declaring the men contraband of war and subject to confiscation just as cannon or horses, he is less clear about what to do with the women and children.

Document 15.3 John Boston, “To Mrs. Elizabeth Boston” (1862)

Slaves began to liberate themselves as soon as the fighting began, pouring into Union lines, seeking refuge, protection, and freedom. Many then took the next step in securing the liberty of their families as they returned south and brought out their wives, children and other family members. After fleeing slavery in Maryland, John Boston found refuge with a New York regiment in Upton Hill, Virginia, where he wrote this letter to his wife who remained in Owensville, Maryland.

Document 15.4 “District of Columbia Emancipation Act” (1862)

On April 16, 1862, President Lincoln signed a bill ending slavery in the District of Columbia. The following document outlines the available compensation to masters for the loss of their slave property, and also lays out the possibility of voluntary repatriation or colonization of former slaves. Over the next nine months, the Board of Commissioners appointed to administer the act approved 930 petitions, completely or in part, from former owners for the freedom of 2989 former slaves.

Document 15.5 “Contrabands Coming Into Camp On the Federal Lines” (1862)

In July 1861, Congress passed the First Confiscation Act, which provided for the confiscation, and de facto freedom, of slaves who were used in the Confederate military effort. In August 1862, it passed a second confiscation act that not only authorized the seizure of the property of persons in rebellion but also specified that all slaves who came within Union lines were captives of war and free. As Union armies moved into the South, thousands of slaves fled to their camps. This illustration depicts “contrabands” entering Union camps in search of freedom.

Source:, May 10, 1862.

Document 15.6 Timothy O’Sullivan, “Fugitive African Americans Fording the Rappahannock River. Rappahannock, Virginia” (1862)

The photograph by Timothy O’Sullivan shows a group of fugitive slaves crossing the Rappahannock River in search of freedom behind Union lines during the second battle of Bull Run in August 1862, just a month before the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation.

Source: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Document 15.7 “The Emancipation Proclamation” (1863)

Emancipation was not one of President Lincoln’s initial war aims – he had sought to save the Union, not destroy slavery. He had first tried to convince slaveholders in the border states to gradually eliminate slavery in return for compensation, but eventually came to see that Emancipation would weaken the Southern economy and so strengthen the war effort. Driven by military necessity and by political pressure, Lincoln released his preliminary emancipation proclamation in the fall of 1862. He read the first draft to cabinet members on July 22 and issued the preliminary version on September 22, which specified that the final document would take effect on January 1, 1863. Then, in finalizing the first General Order of 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln was careful to be precise in his wording. It was through his military powers as commander in chief, not through his executive powers as President, that he proclaimed slaves free, and only in areas that were in active rebellion against the nation and not currently under Union control, allowing slavery to continue in the border states and a large number of Unioncontrolled areas. But in spite of these limitations, the Proclamation gave the Union cause a moral force. The war was now a struggle for freedom.

Document 15.8 “Grand Emancipation Jubilee” (1863)

In addition to printing the official Emancipation Proclamation when it was issued, newspapers carried accounts of the large night-watch celebrations held throughout the Union in anticipation and celebration of the impending Jubilee. For example, in New York City, black abolitionist and clergyman Henry Highland Garnet presided over an emancipation Jubilee. A crowd of both white and black congregants filled the Shiloh Presbyterian Church to capacity. They listened to numerous speeches and closed out 1862 with five minutes of silent prayer before ringing in the new year of freedom with singing and rejoicing. Similar descriptions of such celebrations appeared in the Boston Daily Advertiser, Philadelphia Inquirer, and Chicago Tribune.

Document 15.9 “A Jubilee of Freedom” (1863)

As in many towns and cities, Harrisburg’s black community hailed the Emancipation Proclamation as a new era in the nation’s history even as they acknowledged its shortcomings and recognized that the document was a political move designed to aid the union’s war effort. As shown in these adopted resolutions, the community understood that freedom came with responsibilities, including military service in defense of the nation. In fact, the slave community often viewed military service as a key step in the process of emancipation. A majority of the roughly 180,000 African American troops who fought in the Civil War had been slaves. Their enlistment and service assured them of their freedom, and helped liberate others.

Document 15.10 Thomas Nast, “Emancipation Proclamation” (1863)

In its first issue following the Emancipation Day celebrations of January 1, 1863, Harper’s Weekly published a double-spread illustration by Thomas Nast. Below the rays of “Emancipation,” a scene of African Americans enjoying a comfortable home life is flanked by scenes of the past, including the sale and abuse of slaves, and scenes of the future, including education and fair employment.

Source: Harper’s Weekly, January 24, 1863: 56–57.

Document 15.11 “Touching Story of Contrabands” (1864)

Even after the Emancipation Proclamation, freedom came about by degrees and the death of slavery proved to be agonizingly slow for many. The precise moment when slaves could safely think of themselves as free men and women was not always clear. Some only found out about their freedom after the war, and without mention of the Emancipation Proclamation itself. And freedom was often heavily dependent on the proximity of the army. Many slaves, even before the Emancipation Proclamation, assumed they were free when the Yankees arrived. And even after the Proclamation, many were cautious about exercising their freedom, realistically perceiving that the degree of their freedom often rested with the proximity of federal authorities. Below, a group of men and women reach Port Royal, South Carolina, occupied by Union troops.

Chapter 16: Black Troops

Document 16.1 Thomas Wentworth Higginson, “A Black Regiment” (1862)

At the onset of the Civil War, both the Union and the Confederate Armies were reluctant to arm African Americans. Both governing military hierarchies were operating under the Militia Law of 1792 that specifically banned black enlistment. But both governing military powers changed their policies during the four years of the war. In August 1862, Congress pushed ahead with a Second Confiscation Act in concert with an amended Militia Act that emancipated slaves who were able to labor for the Union forces, and allowed for people of African descent to be mobilized into any branch of the military where they were deemed competent. Regiments of black soldiers also began to organize, with white officers in command. Colonel Thomas Wentworth Higginson (white officer) served as the commanding officer of the all-black 1st South Carolina Volunteers regiment. In this segment of his diary, he details the characteristics of black soldiers.

Document 16.2 R. Saxton, “To Hon. Edwin M. Stanton” (1863))

During the early years of the Civil War, most northern military officers did not want open enlistment for African Americans who might misconstrue the war aims as a strike against slavery. As the Union Army advanced along the coastline, hundreds of enslaved individuals took shelter in the Union camps and offered their services to the northern forces. These “contraband of war” were not to be utilized as fighting forces but could provide labor services to the Union defenses. This would strip the Confederates of the wage-free work force upon which they had become dependent. Below, this letter to the Secretary of War describes how “contraband” men and women will be utilized in the areas of the South administered by Union forces.

Document 16.3 Frederick Douglass, “Negroes and the National War Effort” (1863)

Two years into the Civil War, President Lincoln finally allowed for the enlistment of black soldiers. He hoped black participation in the armed forces would bring an end to the war more quickly. Frederick Douglass announced this opportunity for enlistment to his mostly black audience in Philadelphia on July 6, 1863. The speech also links the ideas of black citizenship and military service, and reassures the listeners that the federal government’s policy of open enlistment would take precedence over any state policies. African Americans flooded the recruiting stations, sometimes traveling to other states so that they could enlist. Douglass interpreted the Proclamation and military service as a positive advancement and he exhorted men to enlist immediately, even supporting his two sons when they joined the 54th Massachusetts Infantry.

Document 16.4 James Henry Gooding, “To Abraham Lincoln” (1863)

In May 1863, the government established the Bureau of Colored Troops to deal with the issues of enlistment, pay and officer selection. One of the most glaring problems was the pay disparity between white and black enlistees. White enlistees were paid $13 per month with a $3 deduction for uniforms, while black enlistees were paid $7 per month after the $3 uniform deduction. Some black soldiers mutinied until the military finally equaled their pay. Below, a black soldier—Corporal James Henry Gooding—writes to President Lincoln about the pay inequities.

Document 16.5 “An Act making Appropriations for the Support of the Army” (1864)

Finally, in June 1864, Congress passed legislation mandating equal pay for black and white soldiers in the Union Army. This revised the inequities and commutation fees from its earlier Conscription and Enrollment Act. Yet it continued with press gangs to bring men into the service against their will. And in regions like Georgia, Alabama, and Texas, Union forces were not numerous enough to provide safety, shelter and freedom to the individuals who wanted to serve.

Document 16.6 Robert E. Lee, “To Andrew Hunter” (1865)

In the South, the Confederate government and military officials studied whether to enlist and arm black men. But they only agreed to arm them when the war was in its last weeks. Writing on January 11, 1865, to Andrew Hunter, a member of the Virginia state legislature who had solicited his views on the subject of black enlistment for the Confederacy, General Robert E. Lee explains the advantages of enlisting black troops into the Confederate Army. He also professes to be willing to offer emancipation to black soldiers and their families as a reward for faithful military service.

Document 16.7 Lt. Colonel C. T. Trowbridge, “General Order No.1” (1866)

By the end of the war, nearly ten percent of the men serving in the military were black. Overall, approximately 180,000 black men served in the armed forces as laborers or combat soldiers. The death toll of black men is estimated at around 38,000 people, from disease or injury in battle. Below, Lt. Colonel C. T. Trowbridge addresses the 33rd US Colored Troops (formerly the 1st South Carolina Volunteers), on February 9, 1966 on Morris Island, South Carolina. He highlights the numerous accomplishments of the black regiment.

Document 16.8 Alfred R. Waud, “African American Soldiers Mustered Out at Little Rock, Arkansas” (1866)

Most black soldiers left the military after the end of the war, and were mustered out—as depicted in this Harper’s Weekly drawing from 1866—although some stayed and joined the occupying forces of Reconstruction, and others continued on in all-black militias. Yet even by the end of the war, military officials were still apprehensive about arming black men, no matter the glowing reports and celebratory illustrations. Congress instituted a new federal policy that established permanent black military units as part of the Regular Army, but they choose to keep the units segregated, with white officers in command.

Source: Harper’s Weekly, May 19, 1866: 308.

Chapter 17: Immigrants

Document 17.1 “The Bonnie Blue Flag” (1861)

The Irish continued to arrive in the U.S. during and after the Civil War. Between 1861 and 1880, around 870,000 Irish immigrants settled in America. They accounted for 17 percent of total immigration to the United States. One of the most popular songs of the Confederacy was even written by an Irish-born immigrant, Harry McCarthy, who was the most famous entertainer in the South and proclaimed his dedication to the southern cause in “The Bonnie Blue Flag” (also known as “We Are a Band of Brothers”). He set the words to an old Irish tune, “The Irish Jaunting Car.”

Document 17.2 “An Act to Prohibit the Coolie Trade” (1862)

Responding to the labor opportunities that accompanied the gold rush, Chinese immigrants arrived in the U.S. from 1848 onward. But economic instability and the growth of nativism meant increased anti-Asian sentiment and working conditions for the “coolies” (manual laborers) were harsh. In 1862, however, the U.S. Congress took action against the American abuse of Chinese immigrants and passed legislation against the excesses of the “coolie” trade.

Document 17.3 “Recruitment Flyer” (1862)

By 1862, more immigrants were desperately needed to provide economic and military labor. Shipping companies actively embarked on recruitment campaigns. In Hong Kong, an immigration broker circulated this flyer below. To provide an even greater incentive, Congress passed the 1862 Homestead Act that offered 160-acre plots to any immigrants whose end goal was citizenship. Thousands of immigrants responded and climbed aboard ships to the U.S.

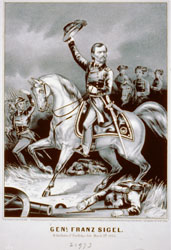

Document 17.4 “General Franz Sigel at the Battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas” (1862)

Born in Baden, Germany in 1824, Franz Sigel journeyed to America in 1852. An active anti-slavery advocate, he joined the Union army and on August 7, 1861, he was commissioned as a Brigadier General. He was promoted to Major General in 1862. Sigel helped to galvanize German–American patriotism and rally German immigrants to the Union effort. In early March 1862, at the Battle of Pea Ridge in Arkansas, over half of the Federal soldiers were German immigrants and Sigel commanded the regiments with these soldiers (the 1st and 2nd Division of the Army of the Southwest), as depicted in this lithograph published by Currier & Ives.

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Document 17.5 St. Clair A. Mulholland, “To Capt. M.W. Wall” (1863)

Born in County Antrim Ireland, St. Clair A. Mulholland emigrated to Philadelphia as a young man. During the Civil War, he was a Lieutenant Colonel with the 116th Pennsylvania Infantry, which was part of the Irish Brigade—an infantry brigade consisting predominantly of Irish Americans. He was promoted to Major General in 1864. Below, he reports on the actions of his regiment to the Irish Brigade’s Acting Assistant Adjutant-General.

Document 17.6 Sinclair Tousey, “Irishmen and Workingmen” (1863)